IoT with PicoW

In the Series "Trying Things Out":

Python on embedded always felt a little bit heretical to me. We're trained to think in cycles and microamps, and the idea of an interpreter running on a microcontroller can trigger instinctive skepticism.

I’ve always written my embedded code in C or C++, even dabbled in Rust. But Python? Never touched it for embedded systems. Why would I? C/C++ gives you full control, performance, and efficiency—everything you want for serious embedded work.

But today, that changes.

I’ve had a bunch of unused sensors gathering dust in a corner of my home. So I decided to build a small IoT project using Python and the Raspberry Pi Pico W. Why the Pico W? Mostly because I haven’t played with it much yet—my go-to boards are usually STM32 or ESP32—they offer more advanced features, especially when it comes to cryptography and firmware-over-the-air (FOTA) updates.

The plan: build a soil humidity and temperature monitor for my houseplants. I’ve always wanted one—mainly because I often forget to water them. I had a soil humidity sensor and a waterproof DS18B20 temperature sensor lying around, so it was the perfect excuse to try something new.

Project Goals

Let’s put down some rough requirements:

- Seamless Home Assistant Integration

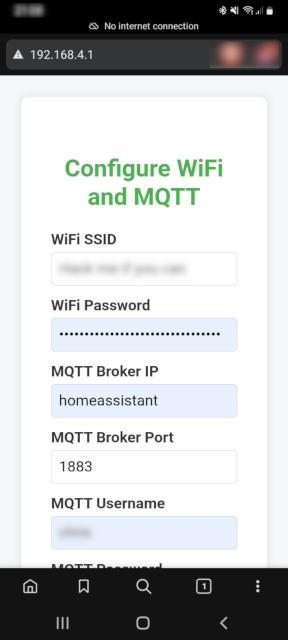

No one wants to deal with manual setup in Home Assistant. The device should support automatic discovery, so HA can detect and configure it right out of the box. - Configurations via HTTP

If the device can’t connect to Wi-Fi or the MQTT broker, it should fall back to Access Point (AP) mode, start an HTTP server, and serve a configuration page. This allows setup from any phone or laptop—no need to reflash or dig into code. - Power Efficiency

We don’t need continuous readings—checking sensor values once an hour is enough. To save power, the device should power down the sensors when idle and use deep sleep between readings.

Wiring

Here’s the basic wiring setup:

- The DS18B20 temperature sensor draws just 1–2 mA, so powering it directly from a GPIO pin on the Pico W is no problem—and it has the added benefit of allowing us to deactivate it on demand.

- The soil humidity sensor pulls around 20–30 mA—too much for GPIO. So I used an NPN transistor (a CB-337-40 I had in my parts bin), which can handle up to 800 mA. Complete overkill, but it works perfectly.

- You can find the exact pin configuration in the GitHub repository.

Coding

Since I already know Python, getting started with MicroPython on the Pico W was pretty easy. Setting up AP mode, serving a config page, and sending sensor data over MQTT all worked without much trouble. The whole process was smooth and worked surprisingly well for an embedded project. Link to the source code.

3D-Printed Case

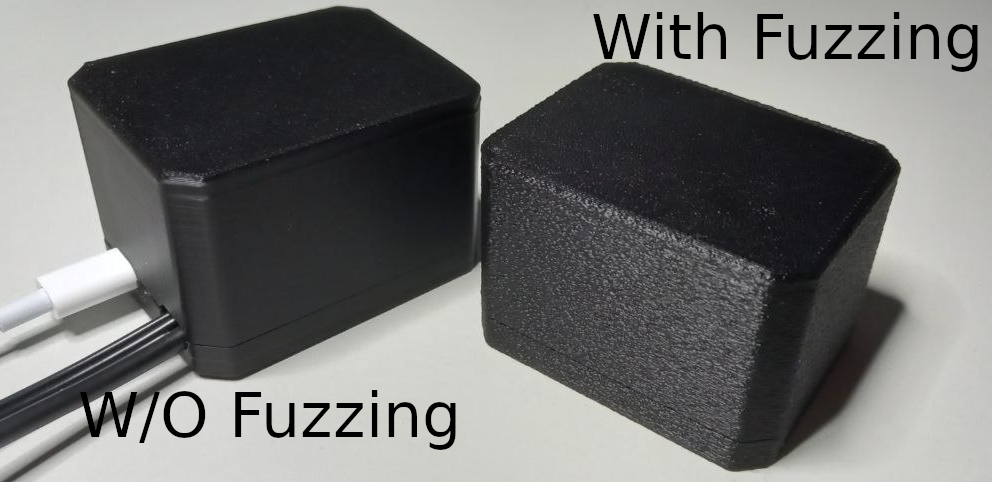

I also designed and 3D printed a small case to house the Pico W and sensors. It has plenty of room for headers and long cables, which makes assembly easy.

If you're using an FDM printer like me, I recommend printing it with "fuzzing" enabled. It hides the print layers for a cleaner look. I used fuzzing at 0.2 for both X and Y axes—see the comparison below.

Setup Device

Setting it up is straight forward:

- Power on the Pico W.

- If it can’t connect to Wi-Fi or the MQTT broker, it starts in AP mode.

- Connect to its Wi-Fi network from your phone.

- Open your browser and go to

http://192.168.4.1. - Fill in your Wi-Fi and (optional) MQTT credentials, hit save, and it reboots.

Done.

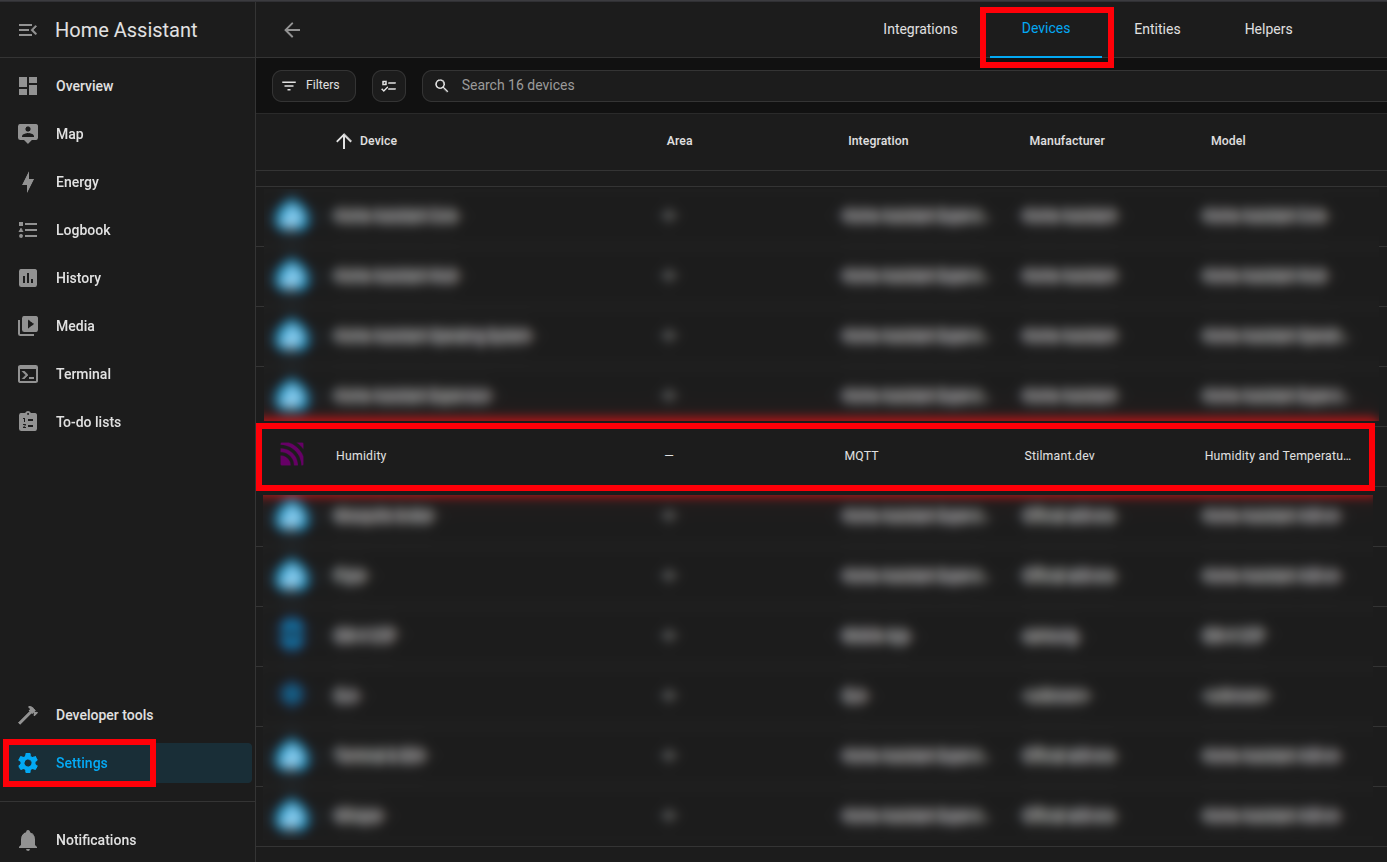

Setup in HA

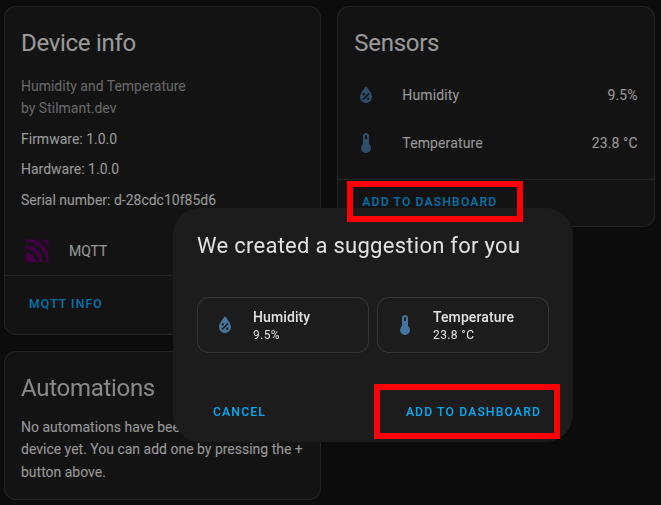

Thanks to MQTT discovery, Home Assistant handles everything else automatically. The device shows up in HA, and you can add the sensor data to your dashboard in just a few clicks.

Final Thoughts

I think that MicroPython on the Pico W won’t replace C/C++ for real-time, performance-critical systems. You’re not going to build a safety-critical motor controller or a secure industrial gateway with it—not yet, anyway. It lacks low-level control, tight timing guarantees, and robust security primitives like hardware-backed crypto or secure boot.

That said, for prototyping, proof-of-concept work, hobby projects, and educational applications? It’s brilliant.

The speed of development is impressive. You can get a Wi-Fi-enabled device online, talking MQTT, serving an HTTP config page, and integrating with Home Assistant in a fraction of the time it would take in C. There’s real value in that—especially when your goal isn’t performance, but experimentation or quick iteration.

So no—I won’t be replacing C in my daily workflow any time soon. But I now recognize Python on microcontrollers as a valid, practical tool for the right use cases.

It’s not about choosing sides. It’s about having more tools in the toolbox.